By Nathanaël Dos Reis / Translation : David Tétard (Dawn of Chivalry)

Three years ago when we decided to build our own military equipment, the problem of the shield design therefore arose. What shape did it take at the end of the 12th century? What material were they made of? What material also to cover the face of the shield? Should the shield be painted? We thus started to do some research and to study the historical sources available. The question of the positioning of the straps was not then at the forefront of our considerations. As a consequence, based on information from forums and our own pre-conceived ideas primarily coming from popular culture, we built our straps like many others do in the reenactment circles, that is to say a strap for the forearm (i.e. a strap that holds the bearer's forearm) and a starp for the hand. We also added a guige, a strap that runs around the neck and that is represented on numerous illustrations of combatnats for our period (late 12th century to early 13th century).

After using the shield for a little while, we started to ask a few questions: what is the purpose of the guige if the shield is equiped with forearm straps that already allow the shield to be held? Is the guige only used for transportation? Or is it used to maintain the shield in place during use? In that case, what is the purpose of the forearm straps?

Finally, we felt that the guige severely hindered and limited our movements.

We asked all our questions to Gilles Martinez during a workshop in 2015. Gilles suggested a line of enquiry: on historical sources from late 12th century to early 13th century, the straps for the forearm are rare. One mainly finds illustrations showing only a guige and hand strap. Although finding this observation surprising, we started our investigations. After two years of research and experimentatation, we now deliver our findings. You can click on the pictures to visualise them in higher resolution and to access the original sources.

Historical Sources

Historical sources showing precisely the inside of the shield are relatively rare. However, some can be found in manuscripts, carvings, effigies, stained glass, etc.

We have decided to start our investigations in the early 12th century in order to learn more about the evolution of straps. We stopped in the 1240's as that period seems to indicate a turning point (with more and more representattions of straps for the forearm and the disappearence of the guige). The chosen historical sources are from western Europe: Holy Roman Empire, Italy (we remind here that we study the province of Savoy that was an important crossroad connecting these regions), kingdom of France and England and Scandinavia. We only considered Spain to identify any existing commonalities.

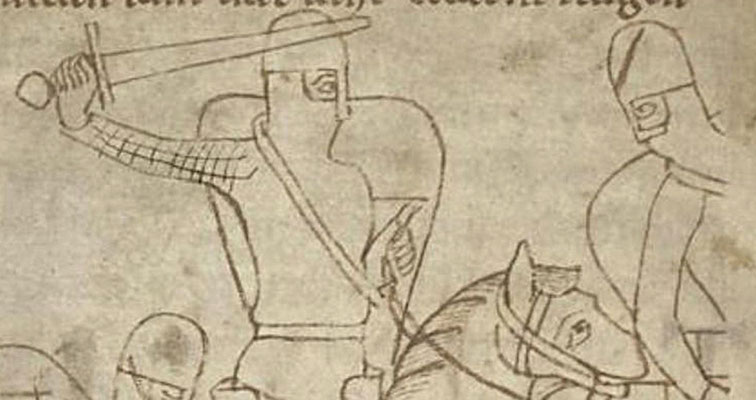

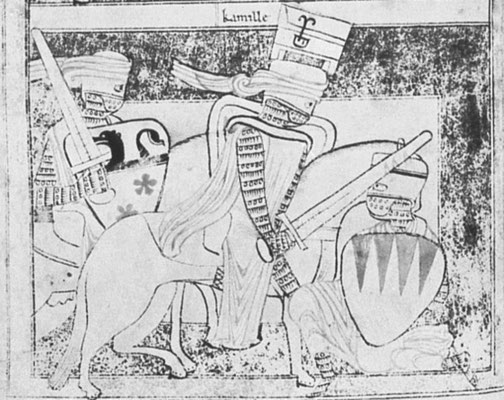

The first thing that was discovered was the almost systematic depiction of the guige for combatants, regardless of them being on foot or on horseback, or wether they are engaded in fighting or not [see illustrations to the right]. The first deduction was that the guige was not only used to hold the shield of horsemen, it was used by foot soldiers as well. Additionally, it was not only used for transportation of the shield but it had a real purpose during fighting.

Historical sources overwhelmingly show shields equiped with only a guige and a hand strap. Illustrations showing shields with a forearm strap are relatively rare. Other strap arrangements also seemed to exist and will be covered at the end of this article.

Some people may argue that the medieval artists may have had a poor knowledge of military equipment. We could suggest that these artists are often from noble families and therefore familiar with military equipment. Additionally, as demonstrated by P. Contamine (La Guerre au Moyen-Age, Collection nouvelle Clio, l'Histoire et ses problèmes. Presses universitaires de France, 1999 p.176, p.185-186; War in the Middle-Ages, Wiley-Blackwell), in the 12th and 13th century abbeys are no longer isolated from the rest of the world. They are instead the heart of ecclesiastical seigniories with their own soldiers to secure their land (Edouard Audouin, Essai sur l’Armée Royale au temps de Philippe Auguste, Champion, Paris, 1913). Finally, it is worth reminding that some old knights retired to abbeys to finish their life in peace. We are convinced that when considering the precision of the illustrations, monks has the ability to inspect, study or be described in detail the military objects they drew. Of course, they are not completely free of errors, approximations or fantasies. Confronted to the large body of work representing only guige and hand strap, we cannot disregard all these sources in one go. We must overcome our prejudice and conduct experiments and reproduction of the equipment to comprehend the use of the shield in the end of the 12th and early 13th century.

Positioning of the Straps

By analysing the historical sources that only represent the guige and hand strap, there appear to be several different possible positioning of the straps. The attachment position of the guige vary from one source to another. We have chosen the attachment method that appears the most representative in the period 1175 - 1220 in the Holy Roman Empire and in northern Italy:

The hand strap was usually located in the top-right third of the shield, with an actual position that varied betwen the top-right corner and almost the middle of the shield.

First of all, on these sources, one end of the guige is positioned on the right, near the hand strap (level with it, sometimes higher, sometimes lower). We chose to place our slightly below the hand strap.

Secondly, the other end of the guige appears to be anchored on the opposite side of the hand strap, in the top-left third of the shield. This hypothesis is supported by illustrations of the inside of other shields.

Here are pictures of the inside of one of our shields. The straping arrangement is composed of one guige going around the neck and of a hand strap in the shape of two crossed strips of leather, similar to what can be seen on the manuscript MS Germ. 2°282 Eneit (1210-1220).

Experimenting

Holding the Shield

Surprisingly, the absence of forearm strap does not diminish the stability of the shield being held. It is in fact perfectly held by the guige alone. The hand strap is used to change the orientation of the shield rather than to hold it up. The weight of the shield is therefore carried by the shoulder of the soldier (thanks to the guige) rather than by its arm. The guige must be tailored to the soldier so that in its loose position, the top edge of the shield reaches the same height as the shoulder, maybe slightly lower. As the guige is the only strap that holds the shield, the leather used for its manufacture must be robust. If that strap happened to break during combat, the soldier would find himself in a difficult situation, struggling to use the shield in an effective manner.

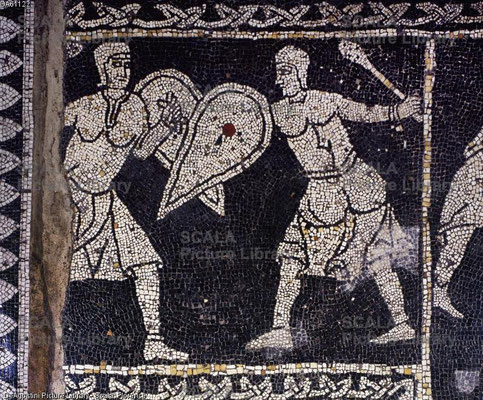

The shield stays rather close to the body. The guige does not allow the soldier to move the edge of the shield forward to a large extent. This seems to be supported by historical sources where combatants appear to have their shield-arm bent at right angle. We have not been able to find any illustration where the shield is held by an outstretched arm when a guige was present. On the contrary, this can be seen in illustrations when the guige is not present [see pictures on the right]. It was necessary to change our way of fighting with this strap arrangement, apparently less geared toward offensive actions. The hand holding the shield stays well in front, towards the centre of the body in a similar posture to that of a boxer with a high guard.

A system that allows a quick change of position

Being free from the hindrance of a forearm strap, the hand holding the shield can get freed very easily.

On German illuustrations can be seen attackers holding their sword with both hands, their shield hanging in their back. Some people have interpreted that as being the very begining of combat using swords held with two hands. However, when the illustrations are carefully studied, it can be noticed that the defender is either on the ground or in a bad defensive position. Our interpretation is that the attacker is using both hands on the sword to give a strong decisive blow to his opponent who is already in difficulty.

On the manuscript MS Germ. 2°282 Eneit, we have two illustrations that follow each other. We can see the same two combatants in two different positions : on the first illustration, both are in a guard position. On the second one, the combatant on the left carries his shield in his back and he's striking his opponent on the helmet holding his sword with both hands. His opponent also carries his shield in his back and is raising the hauberk of his opponent to slip the sword underneath. It must be understood that we have here two illustrations of the same fight. The opponents must have switched from a position holding the shield in their hand to a position with the shield in their back in a fluid and quick move.

This switch is not possible with a forearm strap. The forearm does stay stuck in the strap and the arm is difficult to remove quickly. However, with the straping arrangement we are experimenting with, we could reproduce the switch in combat situation. The forearm is not hindered by straps. One just has to open the hand to let go of the shield. The shield then moves quickly in the back and one can then hold their sword with both hands. This straping arrangement offers a mean to understand the sequence of illustrations in MS Germ. 2°282 Eneit.

We demonstrate the move on a short video in a combat situation. We did not want to choreograph the combat sequence so we directly placed the defender kneeling on the ground, as depicted in the illustration from MS Germ. 2°282 Eneit. On the video, that defender stayed static as the demonstration is not about the combat itself but on the switch between the two positions of the shield.

The possibility of freeing the left hand opens a whole new field of options, most notably in entering the fight. We have an example of this on the German manuscript Speculum Virginium where the left-hand side combatant grabs the hand of his opponent to prevent him from striking a blow.

Moreover, entering the fight when your opponent tries to grab the shield to turn it over, the arm is not stuck and therefore not dragged along with the shield. The combatant simply has to open their hand to free themself from the shield.

Shields in the Back

A lot of illustrations showing shields being carried in the back can be found, some even involving horsemen. The shield is often carried high on the back as the top edge of the shield can be seen behind the horseman's back. The guige runs either around the neck or under the left arm.

Indeed, Bernard Martini notes that in 12th and 13th century texts, shields are mentioned as being held around the neck rather than on the arm: "For example, in the Life of Saint Louis, Jean de Joinville mentions four times that a shield is being carried. Each time, the shield is at the neck." Another example in Lancelot du lac, French text writen around 1225: out of 21 mentions, 17 refer to the shield "at the neck", "hanging at the neck" or "around the neck".

With this strap arrangement, it is also possible to easily grab the shield back in ones hand. With a simple move of the shoulder, the shield is pushed back to the front and the hand strap can be grabbed. We demonstrate the move on the next video. The switch between the shield held in the back and in the hand is fluid and rapid.

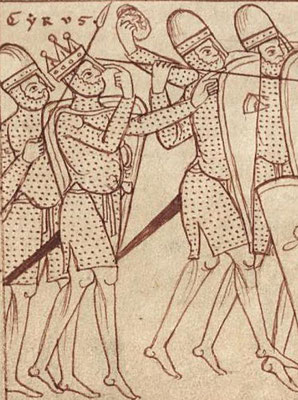

On an illustration in the manuscript Psalmenkommentar mit Bilderzyklus zum Leben Davids can be seen a group of soldiers fleeing, their shield being carried in their back. This shield protects them against potential blows for their pursuers. It can be noted that one soldier is holding the guige with his free hand, possibly to hold the shield against his body or to move it up towards his neck.

Another manuscript also shows a group of soldiers fleeing. On the right-hand side of the illustration, David just severed the head of Goliath and the Phillistines flee before him. The fleeing soldiers also carry their shields in their back.

What about horsemen?

Not being horsemen ourselves, we can only propose our interpretation of historical sources in order to open a new field of study and experimentation to interested parties.

Numerous illustrations indicate that this straping arrangement was also used by soldiers on horseback. There however appear to be one difference: the hand strap is much larger. Clearly, this allows the horseman to squeeze the hand through and hold the reigns. In a combat situation, the horseman can slide his arm back in order to hold both the reigns and the shield strap with the same hand. This may help the rider to move the shield closer to the body and protect himself.

It appears that the same straping arrangement is found for soldiers on foot and on horseback (the difference being the size of the strap as previously mentioned). The horseman should therefore be able to use his shield even when dismounted.

We asked Baptiste Bauer to test our hypotheses during the 2016 edition of Tournoi XIII. According to him, the experiment was conclusive. The shield stayed stable when moving the arm through the strap. Also, he noticed it was relatively easy to remove the forearm from the strap to hold it with the hand if necessary.

One arrangement among others

We do not claim that the straping arrangement that is presented here is the only one that was available or even that it is valid. This arrangement that we have been testing and experimenting with for two years is only one among others. It can still be found in historical sources until the end of the 13th century, but becomes more scarse.

Reading historical sources, there exist other methods to anchor the guige and the hand strap. The guige can be anchored symmetrically on the top edge of the shield, the hand strap can be located lower down or more centrally.

There exist illustrations of shields with straps for the forearm but in that case a guige is not present. Finally, some illustrations let us see the hand strap but not the anchoring point of the guige nor the possible presence of forearm straps.

Even if the system comprising guige and hand strap only is the one that appears to us to be the most representative in the 12th and 13th century, there does not exists ONE single system. So many more investigations to undertake! We present below other sources that we discovered during our research.

Écrire commentaire

Anne (dimanche, 14 juillet 2019 11:15)

Great article! Very interesting findings. Thank you for sharing.

Georg (lundi, 05 avril 2021 15:56)

Very interesting, thank you for sharing the results of your work.

Maurice Ridley (vendredi, 08 avril 2022 01:12)

I do believe you've worked out some very valid points and techniques there that make a lot of sense. I'm looking forward to trying them myself. Good work!